Last fall, I changed many parts of my nonmajors biology class. Some changes were intended to give students a greater role in exploring topics that matter to them; others were aimed at improving information literacy; for still others, I hoped that students would come away with a more unified picture of biology instead of simply memorizing individual facts.

So I did away with exams and replaced them with two projects. For the first project, I gave students a choice of dietary supplements, quack medicines, and legitimate medicines that may or may not work against COVID-19 or cancer. They then individually created a poster or video presentation about the proposed treatment that demonstrated their understanding of basic cell biology, information literacy, and experimental design. (Please add a comment to this post if you’d like to know more specifics.)

It was a big project, so I broke it into chunks and assigned students to groups in which they could compare each other’s drafts, chunk by chunk, to the rubric. I could also skim over their drafts and point the class in the right direction if I saw that large numbers of students were missing the boat on parts of the assignment.

My class had about 60 students, so it was a huge amount of work to design the activity, write instructions for each chunk, monitor the discussion boards where the peer review happened, think of corrective actions if necessary, and — after all was said and done — grade the darn things. But in general, the work they turned in convinced me that they learned more than they would have if I had stuck with the exams.

So far, so good.

The second project was about ecology, evolution, and diversity. Among other tasks, students had to “adopt” an endangered species, describe the threats to its existence, and try to design an experiment testing whether a particular strategy to save the species might be effective. They also had to use their imagination, which is where I think the project started to go sideways. They were supposed to pretend to work for a company trying to make money off the endangered species by using selective breeding to either enhance a commercially valuable trait (think extra-large rhino horns) or reduce a feature that makes the species somehow undesirable (think odorless skunks). I wanted the students to be creative and play with the idea of selective breeding, not to think about the ethical implications — after all, it’s not as if such a company actually exists.

And now, at last, we get to the failure promised in the title of this blog post. Again using their imagination, students were supposed to propose a way that the selectively bred population could evolve into a new species, distinct from the “original” species. I hoped that students would understand that any change can potentially lead to a new reproductive barrier, be it behavioral, anatomical, gametic, you name it. To help them along, I provided a bank of words and phrases they would have to use in their explanations of how speciation might work in their specific scenario.

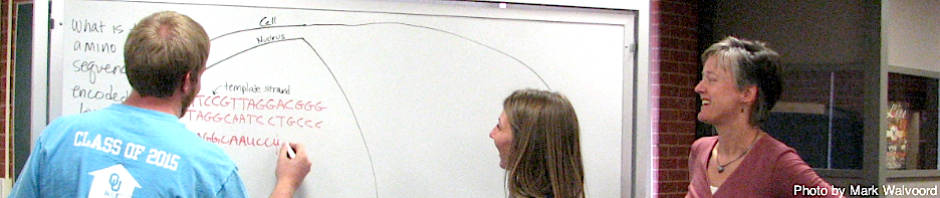

I saw the disaster coming during the draft/peer review stage. Almost all of the speciation explanations were way off base, so I took a fair amount of class time to re-explain the overall concept of the gene pool, how splitting the gene pool can lead to reproductive barriers, and how reproductive barriers lead to speciation. Sure, it’s abstract, but still, the class dutifully nodded after I asked, “Is it clearer now?”

Well, the final assignments revealed otherwise. Here’s a sample. “Speciation is the formation of a new species over time through evolution. A biological species concept helps in speciation and reproductive barriers and uses natural selection. The gene pool helps the population of a species grow and become bigger.”

Still have an appetite for more? “The biological species concept explains that a species is defined by the ability of the population to interbreed. Speciation and natural selection are two reproductive barriers that create different branches of species that are genetically different from one another. This stops interbreeding and creates two separate gene pools.”

Want dessert? “Selective breeding could produce a whole new species of whale by choosing one gene pool to manipulate. Natural selection can also create whole new species. The new species of whale would have to overcome reproductive barriers and make sure the right genes transfer to their offspring. Hopefully, over time we wouldn’t have to have them reproduce in captivity and it would result in the biological species concept.”

Yes, they all used the required phrases. No, they did not coherently explain speciation.

It’s fun to admire the disaster, but what I really need is an effective way to teach an abstract idea that is fundamental to understanding where biodiversity comes from. Other abstract concepts, like atoms and gene function and even the geologic time scale, lend themselves to sketches and models that students can manipulate. Is there such a thing for speciation? I wish I could provide the answer, but instead I’m asking for help. If anyone reading this blog post knows how to do it, I’d love to hear your suggestions.

Oh, and if you’re curious about other things I learned about the projects, here are a few. (1) Written comments at the end of the semester revealed that students generally got a lot out of these projects and preferred them to exams. (2) The quality of the peer reviews was (not surprisingly) spotty. (3) The second project tried to incorporate way too many learning outcomes.

If you want to see the prompts and rubrics for either or both projects, please leave a comment and I’ll happily share. And if you want me to write a future blog post about any other aspects of last fall’s changes, please let me know.

Happy teaching!

Hello, we are just getting ready to start a nonmajors lab based course and were exploring the option of adding an end of semester project as their final. Would love if you could share any details about the first project.

Definitely! I will email you separately with the instructions for both of the projects we did in fall of 2022. Thanks for your interest!

I’d love to see the prompts and rubrics if you are still willing to share.

Sure! I just emailed them to you.

I would like to see the first project details if possible.

Hello! I just sent it to you. Thanks for reaching out!